05.21.07

Posted in Eclipse, programmer productivity at 8:09 pm by ducky

In a previous post, I said that I thought it would be handy to have your source editor color code based on which lines were executed in the prior execution of the code. I mused about merging Eclipse with a profiler in that post, but later realized that I could also use a code completion tool… and then discovered someone had already done it. EclEmma is a fine code coverage tool that is nicely integrated with Eclipse and does exactly what I want.

EclEmma isn’t positioned as a debugging tool, but it sure can be used as one.

Permalink

Posted in programmer productivity at 9:37 am by ducky

From Iris Vessey’s Expertise in Debugging Computer Programs: An Analysis of the Content of Verbal Protocols Systems:

“Experts have more and/or larger knowledge structures in long-term memory, which they build up by the process of chunking. … Chunking refers to the concept whereby humans can effectively increase the capacity of short-term memory by grouping related items into a “chunk,” storing the chunk in long-term memory and the pointer to the chunk in short-term memory. For example, most of us would store KBD as three chunks, while we would store CAT as one since we perceive it as a unit, i.e., as an animal. (See Simon [39].) The importance of knowledge structures to expertise was first established by de Groot [46] and Chase and Simon [22] in their studies of expert and novice chess players. This work has since been replicated in the programming domain by Shneiderman [47] and McKeithen et al. [48].”

This sounds to me like an excellent reason to read Design Patterns.

Permalink

05.20.07

Posted in Hacking, programmer productivity at 12:40 pm by ducky

From the name, I had thought that the Java Modeling Language (JML) was going to be some specialized variant of UML. I haven’t worked with UML, but what I see other people doing with it is drawing pictures.

Instead, JML turns out to be a specification for putting assertions about the code’s behaviour in comments. In that way, it is much more similar to Javadoc than to UML.

With both Javadoc and JML, the author of a method makes promises about what the method will do and what the method requires. In Javadoc, for example, @return int is a promise that the method will return an int, and @param foo int says that the method needs a parameter foo of type int.

With Javadoc, however, the promises are pretty minimal and the requirements are all stated elsewhere (like in the method definition). With JML, the promises about post-conditions and requirements on the pre-conditions can be much more elaborate. The programmer can promise that after the method finishes, for example:

- a particular instance variable will be less than and/or greater than some value

- an output sequence will be sorted in ascending order, or

- variable foo will be bigger than when the method started.

The programmer can also state very detailed input requirements, like that an instance variable can’t be null, that an input must be in a certain range, or that the sum of foo and bar must be less than baz.

This rigorous definition of pre- and post-conditions is useful for documentation. The next programmer doesn’t have to read through the entire method to figure out that foo can’t be null, for example.

Additionally, the JML spec is rigorous enough that it can be used for with a variety of interesting and useful tools. With a special compiler (jmlc), pre- and post-condition checks can get compiled in to the code. Thus if someone calls a method with a parameter outside the allowed bounds, the code can assert an error. (The assertions can also be turned off for production code if so desired.)

But wait, there’s more! The specs are rigorous enough that a lot of checking can be done at compile time. If method A() promises that its output will be greater than 3, and method B() says that it requires the output to be greater than 5, then B(A()) would give a warning: A can give output (between 3 and 5) that B would gag on. See ESC/Java2.

But wait, there’s more! The JML annotations can be used to create unit and tests. The jmlunit writes tests that wiggle the input parameters over the legal inputs to a method, and checks to see if the outputs are correct.

There’s the small problem that it’s a pain to write all the pre-and post-conditions. Fortunately, there’s a tool (Daikon) which will help you with that. Daikon watches as you run a program and sees what changes and what doesn’t change, and from that, generates promises/requirements. Note that those might not be correct. If there are bugs in your program or if that execution of your program didn’t hit all the corner cases, then those won’t be correct. However, it will give you a good start, and I find that it is easier to spot mistakes in somebody else’s stuff than it is to spot omissions in things that I did.

This is all way cool.

Permalink

05.19.07

Posted in Hacking, Maps at 8:08 pm by ducky

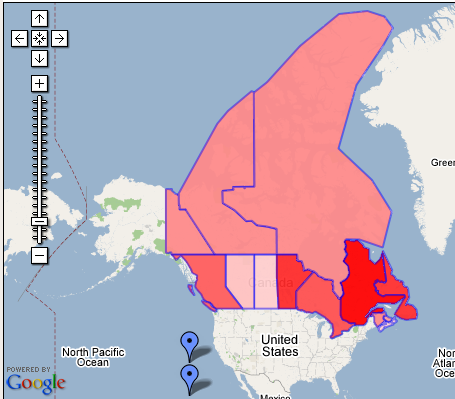

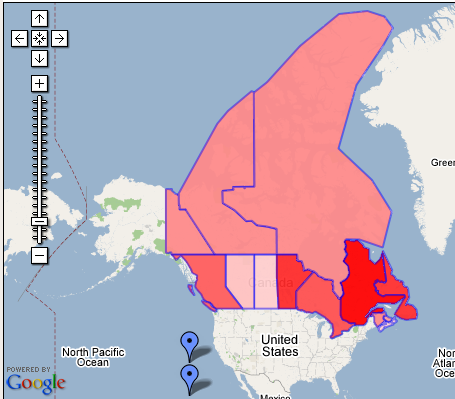

A year ago, while I was in the midst of working on my Census Maps mashup, my Green College colleague Jana came up to me with a question. “I have a table of data about heat pump emissions savings for each province, and I want to make a map that colors each province based on the savings for that province. What program should I use to do that?”

I thought about all the work that I’d done for the Census Maps mashup — learning the Google Maps API, digging up the shape files for census tract boundaries, downloading and learning how to use the shapelib libraries to process the shapefiles, downloading and learning how to use gd, reacquainting myself with C++, reacquainting myself with gdb, debugging, trying to figure out why certain census tracts looked strange, etc, and rendered her an authoritative response: “Use Photoshop”, I said.

I was really dismayed that I had to tell her to use a paint program. Why should she — a geographer — have to learn about vertices and alpha channels and statically loaded libraries? Why wasn’t there some service where she could feed in a spreadsheet file and get back a map?

Well, I finally got tired of waiting for Google to do it, so developed Mapeteria — my own service for users to generate their own thematic maps.

If you give Mapeteria a CSV file (which is one of the formats that any spreadsheet program will be delighted to save as) plus a little more information about how it should be displayed, it will give you back a map. You can either get a KML file (which you can look at in Google Earth) or a Google Maps mashup that shows the map directly in your web browser.

So Jana, here’s your map!

Permalink

05.16.07

Posted in Politics at 2:14 pm by ducky

I thought Ashcroft was completely without positive features, but there are reports that he not only refused to certify a domestic spying program, but that he refused again in intensive care and told off the people trying to take advantage of him in his weakened state.

Now, some changes were made to the domestic spying program, and he signed off on that one, so he’s still way up on my list of disfavored people, but I have to give him some credit for refusing something. I guess he’s only 98% bad.

Permalink

05.14.07

Posted in Hacking, programmer productivity at 9:41 am by ducky

Bil Lewis has made odb, an “omniscient debugger”. It saves every state change during the execution of a program, then lets you use the debugger to step forward through the execution or backwards. You don’t have to guess about why a variable has the value it does; you can quickly jump to the last place it was set.

This seems like an extremely useful way to do things! Bil Lewis wonders why more people aren’t using his better mousetrap: “(I don’t understand why. I’m clever, I’m friendly, I’m funny. Why don’t people go for my stuff? I dunnknow.) ”

I like it, but…

- Its installation is a bit fragile. If you don’t know exactly what you are doing and do everything exactly right, there isn’t a whole lot of help to get you back on track. (If you are a Java stud and don’t make any mistakes, the installation is straightforward.)

- It is not an IDE. It is a stand-alone tool. Yes, its web page says that it can be launched from inside Eclipse, but it sure looks like that just spawns it as a separate process: it doesn’t look like it plugs into the standard Eclipse debugger. That means that it has a separate learning curve and fewer features.

- I worry that for programs larger than “toy” programs, the amount of data that it will have to collect will overwhelm my system’s resources. Will I be able to debug Eclipse, for example?

Now, if it were tightly integrated with Eclipse, like this internal C simulation tool that Cicso presented at EclipseCon, I would be All. Over. It. As it is, I’m probably going to use odb, but only occasionally.

Update 21 May 2007: There is an omniscient version of gdb! It’s called UndoDb.

Update 28 July 2008: There is a commercial Java omniscient debugger called Codeguide, and a research one called TOD (Trace-Oriented Debugger). Also, Andrew Ko’s Designing the Whyline describes a user study of an omniscient debugger, although that fact that it is an omniscient debugger is kind of buried.

Permalink

05.09.07

Posted in Hacking, programmer productivity, robobait at 1:50 pm by ducky

I’m starting to look at a bunch of software engineering tools, particularly those that purport to help debugging. One is javaspider, which is a graphical way of inspecting complex objects in Eclipse. It looks interesting, but which has almost no documentation on the Web. I’m not sure that it’s something I would use a lot, but in the spirit of making it easier to find things, here is a link to a brief description of how to use javaspider.

Keywords for the search engines: manual docs instructions javaspider inspect objects Eclipse

Permalink

05.08.07

Posted in programmer productivity at 10:41 pm by ducky

A theme in Andrew Ko’s papers (which I’ve read a lot of recently) is that a lot of the problems that programmers have is due to making invalid hypotheses. For example, in Designing the Whyline, (referring to an earlier paper, which I didn’t read closely), they say “50% of all errors were due to programmers’ false assumptions in the hypotheses they formed while debugging existing errors.”

It seemed that chasing down an incorrect hypothesis could also chew up a lot of time. I suspect that when coders get stuck, it’s because they have spent too long chasing down the wrong trail.

Yesterday, I had two friends take a quick, casual look at some code to see if they could quickly find where certain output was written out. Both worked forward in the code, starting at main() and tracing through calls to see where control went. At one point in the source, there were three different paths that they could have chosen to trace. The first person chose to follow statement A; the second person chose to follow statement B. Both were reasonable choices, but A happened to be the correct one.

The first person took ten minutes, while the second person spent 30 minutes running off into the weeds chasing statement B. (He eventually gave up, backtracked, and took about ten minutes following statement A to the proper location.)

Implications for programmer productivity measures

The second person took four times as long as the first to complete the task. Was the first person a four times “better” programmer? I don’t think so. From my looking at the code, the second person made a completely legitimate choice. I’m quite happy to believe that on some other task, the first person might make the wrong choice at first and the second person make the right choice.

This makes me even more suspicious of people claiming that there is a huge productivity difference among programmers. The controlled studies that I have seen have all had a very small number of tasks, far too few to make significant generalizations about someone’s long-term abilities.

Furthermore, I think there is sample bias. For a user study, you have to have very simple problems so that people have a chance to finish the allotted tasks in a few hours or less. That favors people who do “breadth-first” analyses of code; who spend a tiny bit of time on one hypothesis, and if that doesn’t quickly give results, move on to the next one.

However, sometimes problems really are gnarly and hairy, and you really do have to stick to one hypothesis for a long time. People who are good at sticking to the one hypothesis through to resolution (without getting discouraged) have value that wouldn’t necessarily be recognized in an academic user study of programmer speed.

How can we reduce false hypotheses?

After a binge of reading Andrew Ko papers last week, I decided to start forcing myself to write down three hypotheses every time I had to make a guess as to why something happened.

In my next substantive coding session, there were four bugs that I worked on. For two of them, I thought of two hypotheses quickly, but then was stumped for a moment as to what I could put for a third… so I put something highly unlikely. In once case, for example, I hypothesized a bug in code that I hadn’t touched in weeks.

Guess what? In both of those cases, it was the “far-fetched” hypothesis that turned out to be true! For example, there was a bug in the code that I hadn’t touched in weeks: I had not updated it to match some code that I’d recently refactored.

While it’s too early for me to say what the long-term effect of writing down three hypotheses will be, in the limited coding I’ve done since I started, it sure feels like I’m doing a much better job of debugging.

Permalink

05.03.07

Posted in programmer productivity at 10:38 am by ducky

As a followup to my previous post about debugging tools, I realized that you could pretty easily add a feature to an IDE that could automatically and very quickly find where hangs were taking place for a certain class of hangs.

What causes hangs?

Hangs happen when something doesn’t stop when it should. This means either

- a loop control structure (for, while, etc) has a test that never is FALSE, so it never stops

- a recursive call doesn’t terminate

- a resource is busy

Let’s look at the loop control case first. It is hugely interesting to figure out the location of the boundary between code that is in the loop and code that is not in the loop. The “lowest” (where main is at the absolute bottom) stack frame that is in the loop will be where the test is not getting the right boolean value, and that’s where you want to start debugging.

For a recursive call, the location in the stack keeps changing, but the same lines of code keep getting executed. Again, the “lowest” frame that is in the loop will be where the recursive structure gets kicked off. Again, that’s an interesting place to start debugging.

If you are hanging because of a resource — a lock or a network connection or something like that — is busy then popping into the debugger should show you exactly where the code is blocked. I don’t have an idea for how to improve the process of finding that because it’s pretty simple.

Tool enhancement

So how do you find the boundary between in and out of the loop?

- Start running in the debugger; pause manually when you are pretty sure you are in the hang.

- Press a “do magic” button.

- Have the IDE set breakpoints at all current lines in all current frames. Set a timeout timer to 0.

- Have the IDE resume execution.

- If execution hits a breakpoint, have it remove the breakpoint, reset the timer and go to step 4.

- If the timeout timer reaches a certain value (1 sec? 5 sec? this will depend upon the problem; the user will need to set this), pause execution again.

- The frame above the top frame that has a breakpoint set will be the frame that has the incorrect loop test. The IDE magic should put the user into the frame above the top frame that has a breakpoint.

This should be relatively easy to do. Again, I’m tempted to do it, but worried about taking time away from other things.

Permalink

04.25.07

Posted in programmer productivity at 1:05 pm by ducky

I read yet another paper by Andrew Ko, this one titled Information Needs in Collocated Software Development Teams and co-authored by Gina Venolia and Robert DeLine.

They collected a bunch of data by shadowing developers of various sorts and got about 25 hrs of data out of it. Mostly they were interested in what kinds of information people need and use, but as a side effect they also logged how much time was spent on what type of activity.

I was curious about how much time people spent on what activity, but they didn’t publish the breakdowns. I can completely understand that — the classification was probably subjective, the sample might have been skewed, blah blah blah. It wouldn’t have had much academic validity.

Still, it is interesting from a non-academic standpoint. It’s another piece of information that helps me create my model of the world. Thus I eyeballed times from a chart in the paper, and this my very imprecise view of how that group of non-randomly-selected developers spent their time:

- 19% – understanding execution behavior (reading code, using the debugger, asking co-workers)

- 18% – writing code

- 15% – reproducing a failure (reading bug reports, setting up test machines, running code)

- 13% – triaging bugs (thinking, talking with other developers)

- 11% – reasoning about design e.g. what is this code supposed to do? (thinking, asking others)

- 10% – non-work

- 8% – maintaining awareness (reading bug reports, reading submission reports, reading email)

- 6% – submitting a change (making sure submission was correct, diffing, running unit tests, using debuggers)

Note that they didn’t define what “non-work” meant. Did writing docs count as work? Did helping marketing out count as work? Did helping a teammate count?

While the numbers seem reasonable if I think about it, if you had asked me how much time was spent on submissions and on triaging bugs, I would have given much smaller numbers. That was surprising to me.

These numbers also show that what one learns in school — how to write a piece of code from scratch — is only a very small portion of what one spends time on in The Real World. While I hear a lot of angst from educators about “communication skills”, I have never seen a class on how to write a good bug report, or how to write a good submission report. I wouldn’t have ever heard of classes on how to write good email messages if I didn’t happen to be a recognized authority on that.

I also haven’t seen much training on how to use a debugger, how to reproduce bugs, or how to triage bugs. Maybe there isn’t much you can teach people on reproducing bugs or triaging them, but there certainly is a lot you can teach people about how to use a debugger.

NB: I was surprised to see that there were nine phone calls in the 25 hours of observation, three of which were work-related. I didn’t know anybody still made phone calls in 2006! I probably got about two work-related phone calls per year in the past four years, and my cell phone log shows that I only get about ten phone calls total per month. The bulk of my communication is email, IM, and SMS.

Permalink

« Previous Page — « Previous entries « Previous Page · Next Page » Next entries » — Next Page »