08.17.09

Posted in Travel at 7:36 pm by ducky

(See also part 1 and part 2 of my Africa postings.)

It’s sort of cliche to say, “the thing I liked best about county X was the people”. We said that about the people in Quebec City, for example. The people in Botswana, however, take it to a whole different level.

There is a concept in southern Africa whose name in Zulu you might be familiar with: ubuntu, or in Setswana botho. It’s not just an operating system, it’s a philosophy of life, almost a religion. The word encapsulates generosity, warmth, openness, and acceptance, but also an acknowledgment of the interconnectedness of all people.

Botho/ubuntu is highly valued in southern Africa; in North America, not so much. I’m not saying that North Americans think that warmth, generosity, openness, and acceptance are bad things, just that they are not valued as highly as other things — like getting the job done quickly and cheaply.

One concrete manifestation of this is that all transactions start with an inquiry about the other: Hello/hello/how are you/fine, how are you/fine, thank you. While this happens in North America, too, you by and large don’t say it to strangers. In North America, when it is your turn to get served, you just say what you want: “One ticket to District 9, please.” Not so in Botswana: all transactions get the full greeting.

Furthermore, while I can’t prove it, I think the Batswana (people of Botswana) mean it.

Valuing botho leads Batswana to be nice, but also it seems like they feel it is their patriotic duty to make sure that tourists have a good time. Botswana has three basic sources of foreign currency: diamonds, cattle, and tourism. That’s pretty much it, and everybody knows that. Everybody understands that diamonds, cattle, and tourism are what funds their roads, their health system, their universities, etc. Thus it is important to the health of their country that tourists keep coming back.

Botswana is also a very small country: 1.7 million people in a country roughly the size of Texas (which has 24 million people). In addition to connections being important (see botho above), everybody knows everybody. (We stopped at a random fast-food place in Francistown at one point, where our Motswana friend B. had lived for about four years, eight years ago. Of the ten or so people in the restaurant, B. knew three. At the hotel we stayed at in Kasane, B. knew one of the desk clerks.) Even if a Motswana doesn’t work in tourism, somebody they know will work in tourism: their brother / sister-in-law / cousin / cousin’s husband’s nephew, somebody.

Finally, Botswana is a politically stable, relatively prosperous country. Botho doesn’t get sacrificed to sectarian violence, nor to hunger. I didn’t see any beggars in Botswana, and the only street hawker we saw had come over from Zimbabwe. (South Africa and Zimbabwe are not prosperous countries, and we did see street hawkers in both of those countries.) There was zero reason to fear getting beaten for my political beliefs, and I never worried about getting mugged.

I was profoundly affected by how nice the people in Botswana were. It was a little bit jarring to come back to the USA, where I wasn’t really supposed to ask gate clerks how they were, and certainly wasn’t supposed to care. I find myself much more wary in North America, with our high number of beggars.

I think that Canadians value botho a bit more than people in the US. So oddly, I think that going to Africa made me a little bit more Canadian!

Permalink

08.15.09

Posted in Hacking, Maps at 9:54 pm by ducky

It might not look like I have done much with my maps in a while, but I have been doing quite a lot behind the scenes.

Census Tracts

I am thrilled to say that I now have demographic data at the census tract level now on my electoral map! Unlike my old demographic maps (e.g. my old racial demographics map), the code is fast enough that I don’t have to cache the overlay images. This means that I can allow people to zoom all the way out if they choose, while before I only let people zoom back to zoom level 5 (so you could only see about 1/4 of the continental US at once).

These speed improvements were not easy, and it’s still not super-fast, but it is acceptable. It takes between 5-30 seconds to show a thematic map for 65,323 census tracts. (If you think that is slow, go to Geocommons, the only other site I’ve found to serve similarly complex maps on-the-fly. They take about 40 seconds to show a thematic map for the 3,143 counties.)

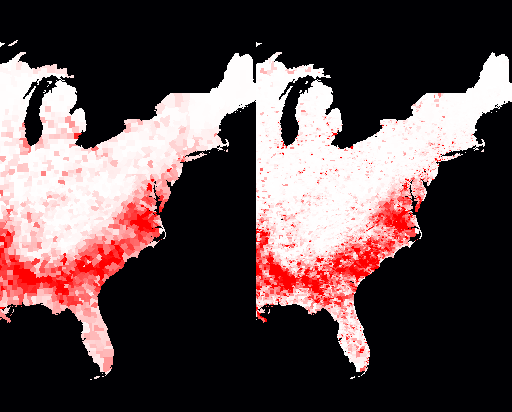

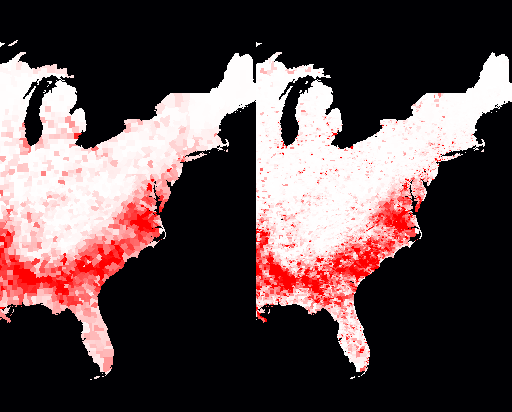

A number of people have suggested that I could make things faster by aggregating the data — show things per-state when way zoomed out, then switch to per-county when closer in, then per-census tract when zoomed in even more. I think that sacrifices too much. Take, for example, these two slices of a demographic map of the percent of the population that is black. The %black by county is on the left, the %black by census tract is on the right. The redder an area is, the higher the percentage of black people is.

Percent of population that is black; by counties on left, by census tracts on the right

You’ll notice that the map on the right makes it much clearer just how segregated black communities are outside of the “black belt” in the South. It’s not just that black folks are a significant percentage of the population in a few Northern counties, they are only significantly present in tiny little parts of Northern counties. That’s visible even at zoom level 4 (which is the zoom level that my electoral map opens on). Aggregating the data to the state level would be even more misleading.

Flexibility

Something else that you wouldn’t notice is that my site is now more buzzword-compliant! When I started, I hard-coded the information layers that I wanted: what the name of the attribute was in the database (e.g. whitePop), what the English-language description was (e.g. “% White”), what colour mapping to use, and what min/max numeric values to use. I now have all that information in an XML file on the server, and my client code calls to the server to get the information for the various layers with AJAX techniques. It is thus really easy for me to insert a new layer into a map or even to create a new map with different layers on it. (For example, I have dithered about making a map that shows only the unemployment rate by county, for each of the past twelve months.)

Some time ago, I also added the ability for me to specify how to calcualte a new number with two different attributes. Before, if I wanted to plot something like %white, I had to add a column to the database of (white population / total population) and map that. Instead, I added the ability to do divisions on-the-fly. Subtracting two attributes was also obviously useful for things like the difference in unemployment from year to year. While I don’t ever add two attributes together yet, I can see that I might want to, like to show the percentage of people who are either Evangelical or Morman. (If you come up with an idea for how multiplying two attributes might be useful, please let me know.)

Loading Data

Something else that isn’t obvious is that I have developed some tools to make it much easier for me to load attribute data. I now use a data definition file to spell out the mapping between fields in an input data file and where the data should go in the database. This makes it much faster for me to add data.

The process still isn’t completely turnkey, alas, because there are a million-six different oddnesses in the data. Here are some of the issues that I’ve faced with data that makes it non-straightforward:

- Sometimes the data is ambiguous. For example, there are a number of states that have two jurisdictions with the same name. For example, the census records separately a region that has Bedford City, VA and Bedford County, VA. Both are frequently just named “Bedford” in databases, so I have to go through by hand and figure out which Bedford it is and assign the right code to it. (And sometimes when the code is assigned, it is wrong.)

- Electoral results are reported by county everywhere except Alaska, where they are reported by state House district. That meant that I had to copy the county shapes to a US federal electoral districts database, then delete all the Alaskan polygons, load up the state House district polygons, and copy those to the US federal electoral districts database.

- I spent some time trying to reverse-engineer the (undocumented) Census Bureau site so that I could automate downloading Census Bureau data. No luck so far. (If you can help, please let me know!) This means that I have to go through an annoyingly manual process to download census tract attributes.

- Federal congressional districts have names like “CA-32” and “IL-7”, and the databases reflect that. I thought I’d just use the state jurisdiction ID (the FIPS code, for mapping geeks) for two digits and two digits for the district ID, so CA-32 would turn into 0632 and IL-7 would turn into 1707. Unfortunately, if a state has a small enough population, they only get one congressional rep; the data file had entries like “AK-At large” which not only messed up my parsing, but raised the question of whether at-large congresspeople should be district 0 or district 1. I scratched my head and decided assign 0 to at-large districts. (So AK-At large became 0200.) Well, I found out later that data files seem to assign at-large districts the number 1, so I had to redo it.

None of these data issues are hard problems, they are just annoying and mean that I have to do some hand-tweaking of the process for almost every new jurisdiction type or attribute. It also takes time just to load the data up to my database server.

I am really excited to get the on-the-fly census tract maps working. I’ve been wanting it for about three years, and working on it off and on (mostly off) for about six months. It really closes a chapter for me.

Now there is one more quickie mapping application that I want to do, and then I plan to dive into adding Canadian information. If you know of good Canadian data that I can use freely, please let me know. (And yes, I already know about GeoGratis.)

Permalink

08.05.09

Posted in Family, Travel at 6:05 pm by ducky

Of all the charismatic megafauna in Botswana, elephants are perhaps the most charismatic and definitely the most mega. We are also friends with Jake Wall, an elephant researcher working with Save the Elephants (see the National Geographic article that he’s featured in!), so we probably knew more about elephants than any other of the Botswana animals. Good thing, as we saw lots of elephants. LOTS of elephants. I am certain that I saw at least one hundred, and maybe two or three hundred.

We saw the biggest herds from the Chobe river next to the Chobe National Park, near Kasane.

There are 50,000 elephants in the 11,700km² park, and in the dry season, many of the ones in the north go to the river in the late afternoon to drink. There are so many elephants there that there are practically traffic jams!

Not only that, but the herds do not run away from tourists in boats. I don’t know if they are just habituated to tourists and how much of it is that groups of primate predators in boats aren’t as threatening as groups of primate predators on land. (How do they know we are predators? Predators have eyes that face forwards.) The elephants kept wary eyes on the boats, but they weren’t spooked enough to move away. Later on the safari, we mostly got to watch animals’ backsides as they moved away from the scary tourists; the river cruise was one place where we saw their frontsides.

In the same way, because we were in boats, the elephants weren’t a threat to us. That meant that the boat captains could bring us quite close. I estimate that we got to within four or five meters of elephants (and crocodiles and hippos!) sometimes.

On our second river cruise, a bachelor herd (males only) swam across the river RIGHT IN FRONT OF US. I knew that elephants could swim, but was quite surprised at how they swam. Unlike dogs or horses, their heads are almost completely submerged and their bodies are completely invisible. All you can see is a little bit of trunk, acting as a snorkel, and the tops of their heads. Their heads rock forwards and back as they swim.

Elephant swimming across Chobe river

All fourteen of the bachelor herd got into the water, but one young male turned abruptly back after walking in up to about his shoulders. Our guide surmised that he was new to the area and afraid of the water. As we left, he was wandering back and forth on the shore, looking across the river at his buddies. I imagined him feeling bereft and forelorn, hating being separated from his herd but also afraid of the dark waters in front of him.

His buddies, once they got across, pulled up hunks of the tall grass in the marshy land on the other side and for all the world appeared to spank the ground with it, then eat it. Our captain explained that they were knocking the dirt off of the roots. (They maybe were standing in a little bit of water — hard to tell from a distance when marsh grasses were everywhere.) When an elephant dies of “old age”, it is usually from starvation. Either the teeth wear down to unusable or they fall out, and then the elephant can’t chew its food adequately. If they knock the dirt off, then that saves wear and tear on the teeth.

On the other hand, sometimes elephants would eat dirt. Yes, really. There are some minerals (like salt) that aren’t plentiful enough in their food, so they will dig holes and eat the dirt. (They might not chew the dirt, I suppose, so perhaps that dirt doesn’t wear down their teeth.)

Elephants feeding each other dirt from a hole they dug

The first pictures, of the elephants at the riverbank, are mostly “breeding herds” — composed of females and juvenile males. As soon as a male starts getting overly friendly with the females in the herd, the mother forces him out! I sure hope that elephants have complex language, as otherwise it seems like it would be a horrible, horrible shock. Imagine being a boy who spends every minute of every day with the same twenty family members, and as soon as your mom sees you checking a girl out, she forcibly runs you out without telling you why! Imagine then having to find a group of other lonely males — with presumably a different social structure — and try to fit in.

The bachelor herds we saw had a range of ages hanging out together. We heard that the younger bulls learned how to do things from the older bulls. (Presumably like how to cross rivers, and also where the good water holes are.)

Bulls do not always hang out together; sometimes they go off on their own. Not being an elephant psychologist, I don’t know if they are socially maladept, bored, tired of being around younger bulls, tired of being around older bulls, or what. Maybe those anthropomorphic emotions don’t even make sense for elephants.

We did observe two elephants being affectionate (or at least intimate) with each other, feeding each other dirt from a hole they had dug — see photo above.

It was not uncommon to see lone bulls — occasionally at very close range!

Jim responding to cries that there was an elephant in our camp

We were taking a siesta in our tent when we heard people shouting that there was an elephant in our camp. We weren’t sure if we were safer inside the tent our outside, and eventually chose to get out of the tent, only to discover that the elephant was only five meters away!

This bull was after seed pods from the camelthorn acacia tree in our camp. He put his tusks around the tree, carefully laid his trunk up the tree trunk, and shook the tree, making pods rain down. He hoovered the area of pods and then sauntered off, totally nonchalant and disinterested in us.

Bull elephant harvesting camelthorn acacia seed pods

I was surprised at just how quiet elephants are when they walk. As I mentioned above, the elephant in our camp was 5m away and we never heard him. Not a thing. They are so big that you’d expect the ground to shake as well, sort of like a truck going by, but no, not a thing. When walking, they have three feet on the ground at any one time, and have big poufy feet, so they are incredibly stealthy. Here’s how big their feet are compared to mine:

Tracks of the elephant that went through our camp

Later on the trip, Jim and I heard a great deal of splashing around while we were visiting the camp latrine, which that night only had distance as its privacy guard. The splashing noise went away before we finished up, and on our way back we encountered a (very uncomfortable/embarrassed) guide who wanted to warn us that an elephant had swum across the river and landed right near us, but didn’t really want to intrude upon us in the latrine! Once the elephant got out of the river, we heard nothing, even though the splashing sounded quite near.

Did that frighten us? No. Maybe it should have, but it didn’t. The elephant that passed the latrine could probably smell us (and the latrine), we were not advancing upon it, it would have to go through some bushes to get to us, and elephants are usually not aggressive unless they are in musth (a condition similar to erustrus in females, characterized by extreme randiness, aggression, and a strong and distinctive odor) and we didn’t smell anything funny. We also only heard one animal splashing, which meant that it was unlikely to think we were threatening its child.

We did see adult females protecting a baby elephant quite fiercely a few days before: note that there are four adult females forming a defensive ring around the baby, barely visible (cyan arrow points to its tail). They were also trumpeting and flapping their ears.

Four female adults protecting one baby elephant

While elephants’ walking is nearly silent, the same cannot be said for their crapping. Their dung comes out in volleyball-sized balls, and like horses but unlike dogs (or lions, as we observed later), elephants don’t stop and squat to defecate, but just lift their tails and keep on walking. That means their dung falls from a great height — two or three meters up. Boom! Boom! Boom!

Elephant dung

The shape is such that, well, I will never look at Rolo chocolates the same way again.

On our river cruise, we were quite surprised to see baboons apparently eating elephant dung. Our guide explained that elephants have poor digestive systems. (Elephants pass so much fiber in their dung that people make paper out of it!). Their digestive system is so poor that frequently it lets fruit and nuts escape undigested. Baboons would thus root through the elephant dung in order to find those fruits and/or nuts.

Baboon eating elephant dung

As you can see, I was fascinated by the elephants.

Permalink

Posted in Family, Travel at 5:42 pm by ducky

Jim and I, having no kids of our own, borrow nieces and nephews when they turn (about) fourteen. We had a friend from Botswana who encouraged us to visit, and The Niece was up for it, so we went to Africa! This post talks a little about where we went, how we got there, where we stayed, what the accommodations were like, etc. This post will have almost no observation/analysis/personal notes: it probably isn’t that interesting unless you really like Jim and/or I, or you are planning/thinking about a trip to Botswana yourself. (See the next postings for analysis and personal notes.)

We spent twenty-four days total away from our home, although we spent about seven days getting there and back: one day from Vancouver to Seattle (via Bellingham to pick up The Niece), one night to Frankfurt, one day in Frankfurt, one night to Johannesburg, one day drive to Botswana, and then the reverse (except we flew to Jo’burg instead of driving).

The Safari

The centerpiece of the trip was a seven-night/eight day overland (i.e. driving) safari with Chobezi, camping for one or two nights in one place, then driving to the next interesting place. We travelled in a group of eight: us three, two Belgian men in their early twenties, one guide/driver, and one cook.

We found and booked the trip online (and when I say “we”, I mean “Jim”), with what turned out to be a South African booking agency. This meant that we knew very little about what the safari would be like. We knew where we would be stopping, and we knew that we were going overland and camping in tents with foam matresses, but that was all we knew. We knew so little that we even had trouble rendezvousing with Chobezi at the pickup point!

We camped at four places: at Serondela and Savute Marshe in the Chobe National Park, Moremi Game Reserve, and an island in the Okavongo Delta.

A typical “moving” day would have us get up around 0630h, eat breakfast, pack our gear, tents, and sleeping rolls, wait for the guide and cook to pack everything else (they turned down help), and drive to the next site, looking for game along the way. We’d set up our tents and bedrolls, then take a siesta, sunbathe, hang out, whatever, until about 1630h, when we’d do an evening game drive before dinner. A non-“moving” day would be the same except that we’d go for a game drive early in the morning and not tear down/set up camp or drive to the next site.

We rode around in a “safari car” or “safari truck” — a converted Land Cruiser with elevated bench seats. The truck we used on our safari has five seats plus some storage in the back, plus it hauled a trailer full of stuff when we moved camp. I believe most safaris rely more heavily on airplanes to get people from one place to another; I don’t recall seeing another safari car with storage.

Our safari car

Here are some other safari cars:

Some other companies' safari trucks

The tents were quite big. The Niece and I could stand up in them.

Ducky Standing up in tent

I had never seen bedrolls these before: they were relatively thick foam matresses, with sheets, pillow, and a comforter placed on them, that we could zip up and roll up.

Bedrolls unfurlled (L) and in bondage (R)

Bedrolls rolled up

The tents and bedrolls were heavy, but because we were car camping, it didn’t matter.

Camp hygiene

The camp had a it latrine with a toilet seat frame over it, and canvas walls set up around it. Jim once commented that in terms of value per ounce, the toilet seat was way, way up there!

Next to our tents they put little canvas bags that served as wash basins. Every morning, they would put hot water in the basins for us to wash with. That was really nice!

We also didn’t realize it until near the end, but we had a shower available as well. Apparently the first day, our guide asked me if I wanted a shower. “Maybe later”, I said, and he waited for me but I never got around to asking. I don’t remember this: probably I thought he was kidding. (A shower? While camping?)

At our second stop (at Savute Marsh), we stayed in a campground, with hot showers and sinks and flush toilets and everything. They also had neat washbasins with built-in washboards, so clearly you were allowed (encouraged?) to wash your laundry in the sink.

There were probably twenty campsites at the Savute Marsh campground, filled mostly with self-driving South Africans. You would think that would impede the wildlife viewing, but in fact did not, as you will read about in my elephants post.

Camp food/cooking

Cooking was done on an open fire. They brought along something that looked like an iron coffee table, and put that over the fire.

Kitchen facilities

Breakfast consisted of cold cereal, tea, porridge (oatmeal), and fruit. On moving days, lunch was usually sandwiches (cold cuts), potato salad, and fruit. Dinner was always a hot meal, with a meat course, starch (potatos, rice, or “pap” — sort of corn/maize porridge), and a vegetable dish (e.g. carrots and potatos). The food was really, really yummy — the cook did a great job.

Jim and I normally try to eat vegetarian, with Jim being better at sticking to his values than I. I wimped out and ate the meat in Botswana because it was just easier. (Jim had told the South African booking company that we were vegetarians, but that piece of information never got to the guides.) Jim just didn’t eat the meat for a few days. The cook and guide noticed, and asked Jim, who said that he preferred to not eat meat.

The next day, the cook announced that “for the man who does not eat meat, I fixed something special.” With a flourish, he revealed… chicken! (In many languages, “meat” means “mammal meat”.) Faced with that level of attentiveness and care to his needs, Jim (sigh) ate the chicken.

Mokoro camp

For our last two days, we said goodbye to our driver (although we kept our cook) and went out to an island in the Okavango Delta by boat(s). First we took a speedboat to the Boro village, where we transferred to mokoros — poled dugout canoes — for a two-hour water voyage to our camp.

Getting ferried by what are essentially African gondolas sounds very romantic. The reality was less so. The boats were very tippy, so you had to be careful about shifting around. The seats were basically institutional plastic chairs with no legs, just dropped into the boat, so weren’t that comfortable. We went there in the afternoon and came back in the morning — and the camp was west, so we had the sun in our eyes both times. Perhaps because it has been an extremely wet year, there were thousands of gnats, which hovered right at sitting-person-level. To catch the gnats, many water spiders built webs right at sitting-person-level. (Note: neither the gnats nor the spiders bit. They were just annoying.)

Gnats during Mokoro ride

One of the Belgian youths turned his seat around so that the back of his head caught the gnats and spiders, and the sun was not in his eyes. That would have been much more pleasant. Going out in the morning and back in the afternoon would have also been more pleasant.

We went on a game walk on the island, something that we couldn’t do elsewhere. In other areas, we had been pretty much stapled to the truck because of the small but real danger from lions. While we did get a safety lecture before our walk on what to do if we encountered lions, hippos, snakes, or wildebeests, I presume that the dangerous animals are rare on that island. (We did not see any lions, hippos, or snakes, and the wildebeest were a long way away.)

It was nice to get some exercise, and we saw larger herds of animals than we did from the safari truck. (The truck is noisy. It can’t really sneak up on a herd the way we could on foot.) However, we couldn’t get as close on foot, in part because of the need to be stealthy, in part for safety reasons. While we saw lions from several meters (and in one case, ONE meter, see below) from the truck, on the walk we were usually more like 500m or 100m from herbivores.

One example of how close we got in the truck

We also didn’t see much on the walk that we hadn’t already seen from the truck, aside from an aardvark den (a hole in the sand).

The locals who guided or poled us to the island did sing and dance for us on the second night, and we got a mini-tour of their village, and that part was nice. Aside from that, however, I could have done without the Okavongo Delta part of the tour.

Non-safari

We spent several days in Gaborone (“Gabs”), the capital. We ran out to tour the diamond mine in Jwaneng the day after we landed (since the mine only gives tours on Fridays). The mine could have been any heavy equipment plant in North America, except that the second language was Setswana and not Spanish (US) or French (Canada) and there were two more baboons than I would have expected in North America.

Ducky looking out over open-pit diamond mine

We spent the weekend wandering around Gaborone — checking email, letting Katie run on a treadmill at a gym, shopping for things the airlines ban, buying local GSM chips for our cell phones, trying and failing to find local maps, wandering around shopping malls and bazaars — and waiting for our friend B. We were supposed to leave Gabs on Sunday, but our friend B. sadly had to go to a funeral on Sunday, so we had an extra day in Gabs.

We were going to go to the Khama Rhino Sanctuary in Serowe, but because of the funeral, we had to cut something, so we cut the rhinos. We found out later that our friend B. is from Serowe; had we realized that, we would have cut something else.

Serowe is also the hometown of Sir Seretse Khama, the first president of Botswana. Botswana is, unlike its neighbours, a bastion of peace and (relative) prosperity, in large part due to this one amazing man. Please pause now and read his Wikipedia entry before going on to my next Africa journal blog posting.

Permalink